It’s Time to End Security Neglect in Smaller Teams

By borrowing concepts from observability, security observability can enable a security operations team to understand risks and incidents in a more holistic way than the traditional ‘rapidly growing pile of notable events’.

I’ve been speaking with a lot of SIEM (Security Incident and Event Management) engineers and MSSP (Managed Security Service Provider) analysts lately, and a common thread in the conversations has been that smaller organizations struggle to attend to their security needs.

While there is an abundance of quality open-source software, it seems there’s a massive lack of people to do the needed work. Experienced security professionals have great instincts for their environment, but checking that gut feeling with some hard data is only prudent. To that end, we’ve been evaluating the security market from a few angles here at Observe. You’ll be seeing some of the meatier research soon, but here’s an initial take based on social media data evaluation. I think there’s a way out of this mess via security observability, but first, let’s confirm that the mess is there.

Methodology

We started with two questions, “How much operational security headcount is out there?”, and “Does it cluster with larger or smaller organizations?” We also decided to use an external measurement to answer those questions: instead of looking at more formal self-reporting by organizations, we looked at the social media information that individual employees post to LinkedIn.

To form a set of candidate teams for evaluation, we used a list of five hundred “companies” (in LinkedIn terminology), across different sizes, industries, and regions. For each organization, we then used a LinkedIn search for current employees with titles matching “security”, “threat”, “cyber”, “soc”, or “incident”. Titles that indicated field personnel (consultant, trainer, &c) and titles that indicated application security engineering were filtered out. While those can be useful groups to draw security operations support from, they’re not dedicated to operational security.

We used those search results to answer two questions:

- Is there a security team (greater than one person with a title match) at all?

- If so, is that team small (less than ten people), or large (ten or more people)?

Lastly, we split the organizations by headcount: small (less than two hundred people), medium (two hundred to less than one thousand people), and large (one thousand or more people).

The hypotheses we brought to this process were as follows:

- Smaller organizations are most concerned with lights-on-doors-open operations and compliance and may defer security

- Larger organizations are more likely to have increased security investment for a variety of reasons, such as more stringent compliance needs, or the concept that they present a bigger target for attackers

Results

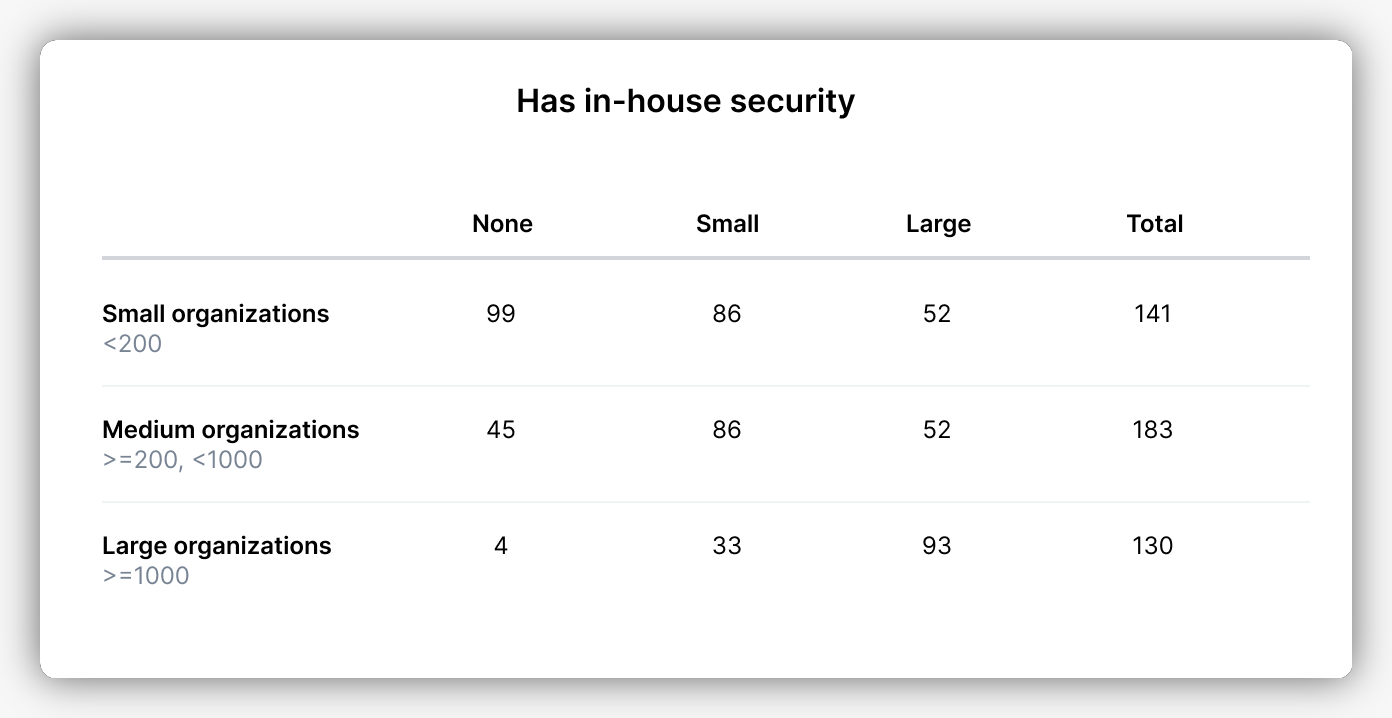

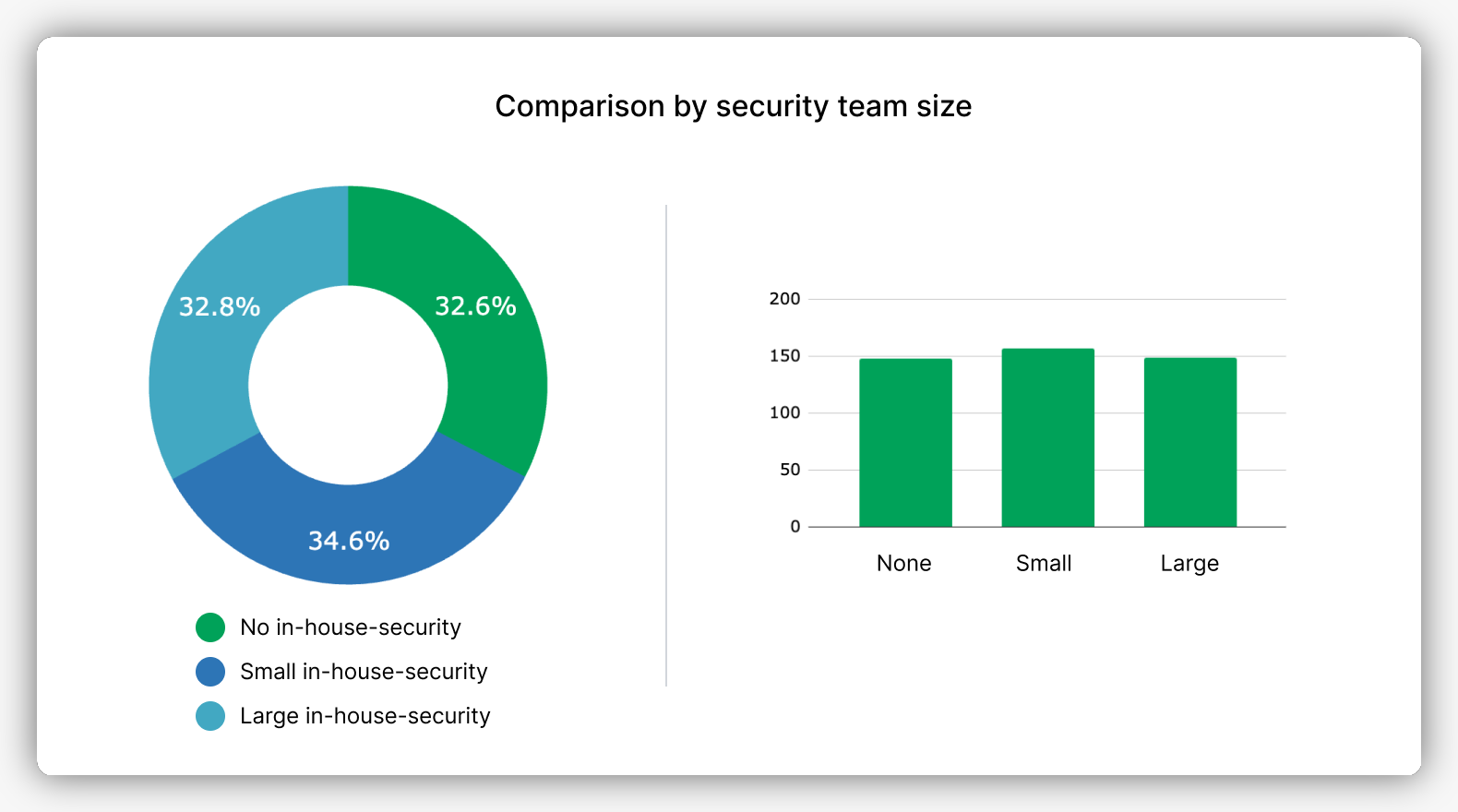

Our results held up those hypotheses pretty well. With an N of 454 (after filtering organizations without a LinkedIn page) here’s what we found:

The distribution of no, small, and large team size is remarkably even across all organizations. Like the Future, IT Security is here, but not evenly distributed. Some portion of that “No” team finding may be false; a company that has wholly outsourced responsibility might not have people with security titles. On the other end of the spectrum, an organization with very high-security concerns may have a policy against employees using LinkedIn to identify themselves or their role (though this may have been mitigated by filtering out organizations that do not have their own LinkedIn presence).

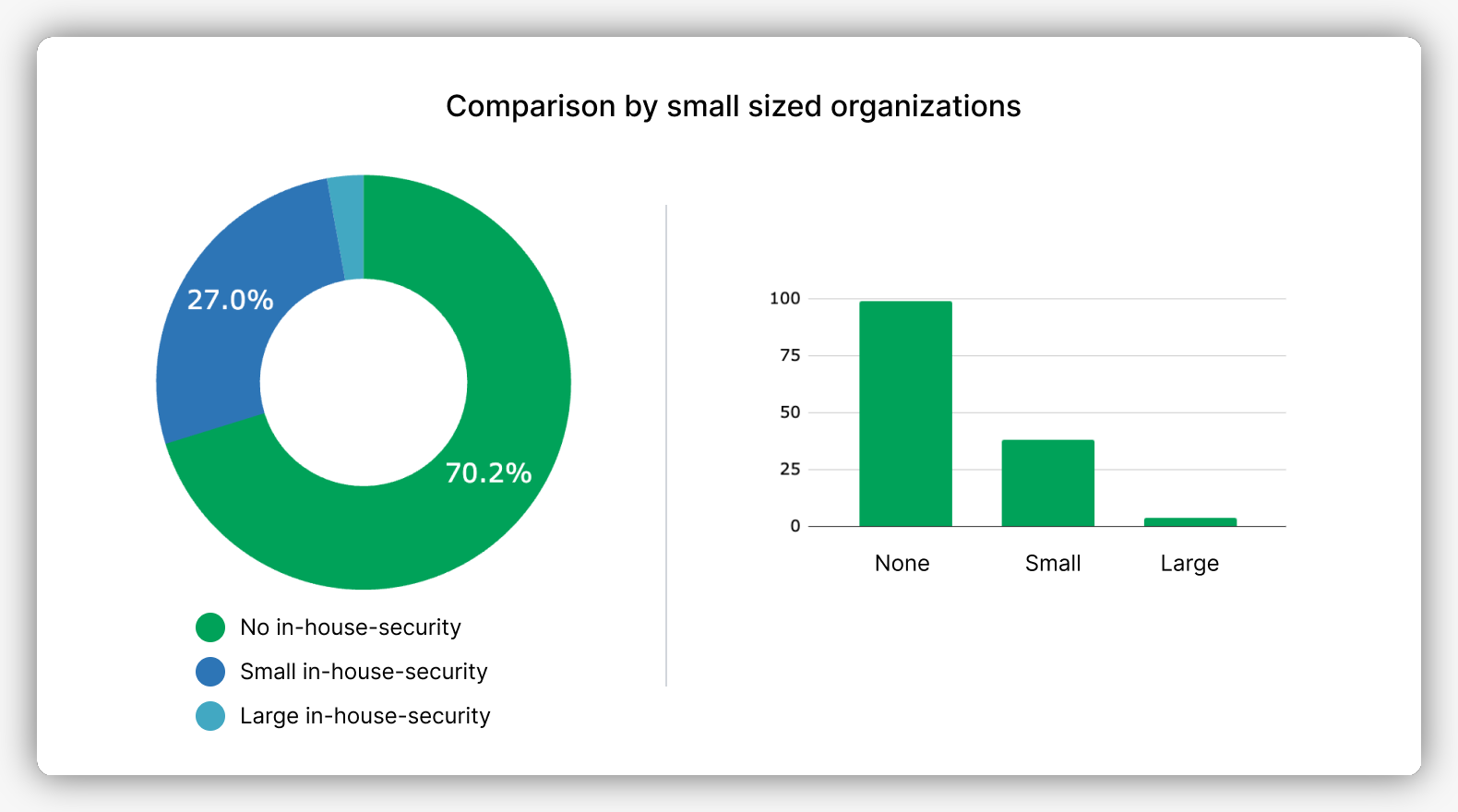

Our next assumption is that a smaller organization is more likely to do without a dedicated in-house security team, either outsourcing or deprioritizing in favor of lights-on-doors-open or compliance requirements. The data appears to align with that assumption, with 44% of small organizations showing no security team footprint via public LinkedIn data. There is often a CISO or a Security Director in these shops, but without dedicated in-house help, we assume they’re working with shared resources from non-security teams and/or services vendors. That means borrowing help from other parts of the organization and hiring temporary consultants or MSSPs.

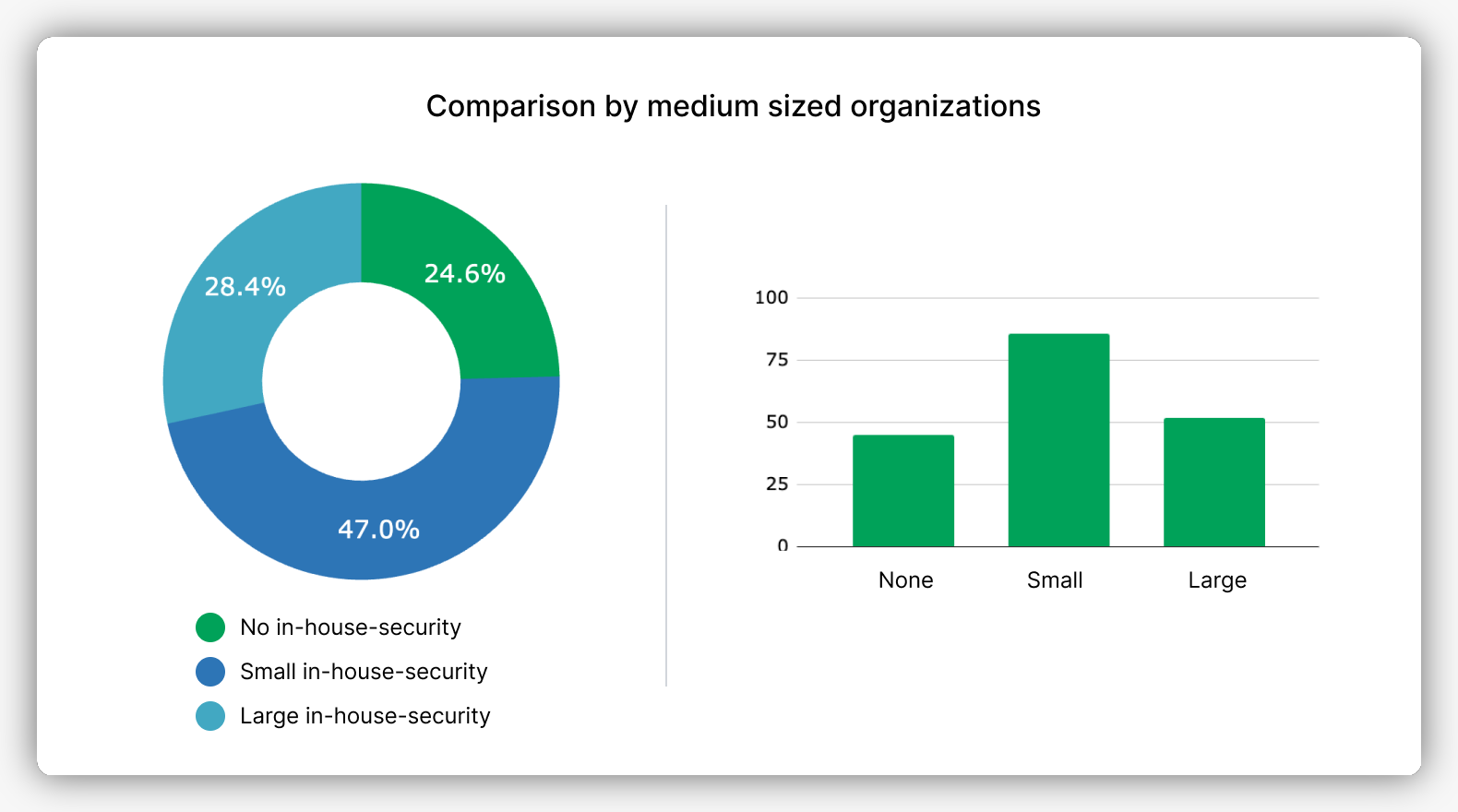

Presuming that this is a scaling concern, we would expect a medium-sized organization to show lower no-team numbers, which is the case.

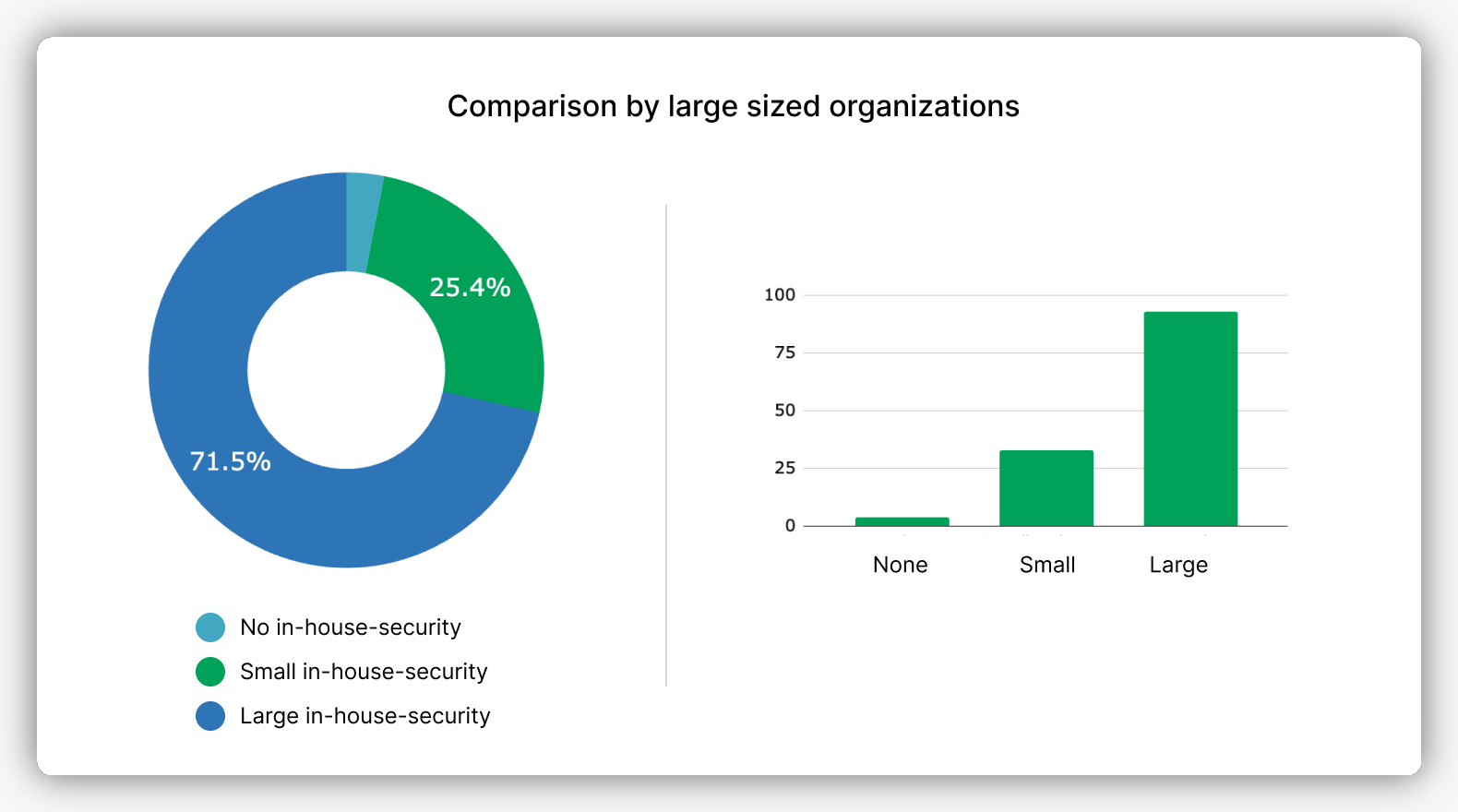

Lack of a security team drops from 70% to 25% as the organizations get larger, indicating that this is an important hire. However, the team is still not large.

The hypothesis continues to hold with large teams. We expect that a larger organization is likely to have more stringent compliance requirements that will drive more hiring of security people and the use of security products. Furthermore, a large organization is arguably more likely to be attacked, if only because they have more internet surface area. An organization with more headcount is more likely to have name recognition, revenues, and relationships that will make them a more attractive target.

There are several other anecdata-based takes and prejudices to consider from these findings. One notable item is that a small company that is not hiring people with security-related titles may not be throwing caution to the wind. They certainly care, even more than a larger organization in some cases: where an international firm can shrug off a breach and data loss, a smaller team might be sunk. Interviews with these sorts of companies suggest a lot of shared responsibility, similar to DevOps (though the term DevSecOps doesn’t fit, being more about application security). Sharing responsibility for information security operations with the “regular” operations team is the future, just as infrastructure ops is now shared with developers.

Another notable from discussions with the larger shops is that not all large headcounts are shaped equally. A large InfoSec team could be one big flat Security Operations Center (SOC) processing tickets with few opportunities to escalate problems, or it could have several significantly different roles and responsibilities. Is it better to defend with a dozen Tier 1 SOC analysts or a dozen Tier 4 threat hunters?

Some organizations also make it difficult to distinguish field engineers or application security engineers from IT Security team members, using levels in their titles or sharing responsibilities across roles. While a larger organization is likely to have more roles and levels than a smaller one, any team in any organization can be asked to do more with less, load-share with other teams, and otherwise stretch the definitions of what a role looks like. A large headcount doesn’t always mean the attitudes and budget of a wealthy international firm.

Recommendations

So, if only big firms can afford security operations, is the best advice to “Get big so you can afford a security operations team”? That’s hardly useful. Rather, we should work to enable the reality for smaller organizations: everyone pitches in together, and security operations are a shared responsibility. It’s also not great to recommend DevSecOps: while it’s certainly great to integrate secure development practices earlier, there are few day-to-day SecOps in DevSecOps. Instead, IT teams are asked to “Do what you can with what you have.” Security Observability uses the external outputs of a system, its logs, metrics, and traces, to infer risk, monitor threats, and alert on breaches. Security professionals use this close observation of system behavior to detect, understand, and stop new and unknown attacks. By borrowing concepts from observability, security observability can enable a security operations team to understand risks and incidents in a more holistic way than the traditional “rapidly growing pile of notable events”.

SIEM has been attractively positioned to small and medium organizations as a content and integration-rich entry point. The idea is that by buying that product; you get access to dozens of rules and add-ons specific to the other products that your organization runs on. Sadly, the reality of SIEM has been more brittle. Each integration has its specific versioning and configuration requirements, each rule only works with properly abstracted data, and each alert expects that the customer can decide if it’s important or not. The whole creaky stack of transformations and rules needs continual maintenance, and without trained in-house people that means costly professional services time.

Smaller organizations without dedicated professionals and dedicated tools need a better solution than SIEM. Because security operations aren’t performed by separate teams, security data and tooling cannot be in a separate system from operations data. Instead, security issues should be treated as operational issues, as risks of system failure. Security observability can be spun to mean many things: scanning some vendor pages, I found about a dozen firms that use it to describe their traditional SIEM which smaller organizations still can’t afford to operate. Instead, we should help these smaller organizations use their observability platforms to support security needs.

The Observability Cloud gives customers the power to identify attacks, the cost structure to afford security countermeasures, and the user experience to merge security use cases with operational use cases. It breaks the huge spend on tooling and people associated with more traditional SIEM approaches. What’s even better, it lets you see how systems and people interact over time. Better security for less spend with Observe.

Of course, this survey was not the be-all and end-all of our data collection at Observe, it’s just a starting point. Look for results from our 2023 State of Security Observability survey, coming soon!